Under normal circumstances, the vocal cords meet in the midline during phonation. On inspiration, they move away from each other. They return toward the midline on expiration, leaving a small opening between them. When laryngeal spasm occurs, both true and false vocal cords lie tightly in the midline opposite each other.

The recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN) carries both abductor and adductor fibers to the vocal cords.

Selmon’s law: The abductor fibers are more vulnerable, and moderate trauma causes a pure abductor paralysis. Severe trauma causes both abductor and adductor fibers to be affected. N.B.:- Pure adductor paralysis does not occur as a clinical entity.

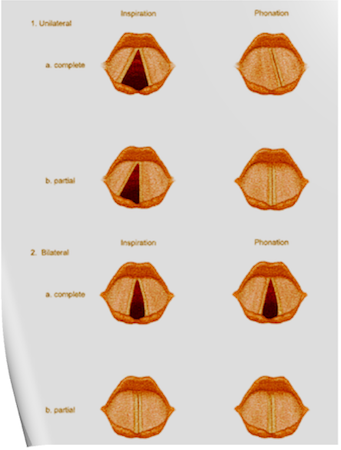

Scenario 1- PURE UNILATERAL ABDUCTOR PALSY: As adduction is still possible on the affected side, the opposite cord come and meet in the midline on phonation. However, only the normal cord abducts during inspiration.

Scenario 2- COMPLETE UNILATERAL PALSY OF THE RLN: Both abductors and adductors are affected. On phonation, the unaffected cord crosses the midline to meet its paralyzed counterpart, appearing to lie in front of the affected cord. On inspiration, the unaffected cord moves to full abduction.

Scenario 3- BILATERAL INCOMPLETE ABDUCTOR PALSY: When there is incomplete bilateral damage to the recurrent laryngeal nerve, the adductor fibers draw the cords toward each other, and the glottic opening is reduced to a slit, resulting in severe respiratory distress.

Scenario 4- COMPLETE BILATERAL PALSY OF THE RLN: With a complete palsy, each vocal cord lies midway between abduction and adduction, and a reasonable glottic opening exists.

Thus, bilateral incomplete palsy is more dangerous than the complete variety.

Scenario 5- DAMAGE TO SUPERIOR LARYNGEAL NERVE/S: Damage to the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve or to the superior laryngeal nerve trunk causes paralysis of the cricothyroid muscle (the tuning fork of the larynx), resulting in hoarseness that improves with time because of increased compensatory action of the opposite muscle. The glottic chink appears oblique during phonation. The aryepiglottic fold on the affected side appears shortened, and the one on the normal side is lengthened. The cords may appear wavy. The symptoms include frequent throat clearing and difficulty in raising the vocal pitch.

Scenario 6- TOTAL BILATERAL PARALYSIS OF VAGUS NERVES: This affects the recurrent laryngeal nerves and the superior laryngeal nerves. In this condition, the cords assume the abducted, cadaveric position. The vocal cords are relaxed and appear wavy. A similar picture may be seen after the use of muscle relaxants.

N.B:- Topical anesthesia of the larynx may affect the fibers of the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve and paralyze the cricothyroid muscle, signified by a “gruff” voice. Similarly, a superior laryngeal nerve block may affect the cricothyroid muscle in the same manner as surgical trauma does.

Reference: Benumof and Hagberg’s Airway Management, Third edition